GOOD GRIEF!

The drive to understand experience, and make sense of the world is as vital as the need to breathe – to eat.    And so it is that trying to understand and give meaning to life’s final moment is equally significant.   This may be a vain attempt to make sense of the inexplicable but for the moment the process of coming to terms with and accepting Josh’s death has inevitably raised the issue of our own mortality – the fear it holds, even the release it promises.    A year and some months on from this tragedy I am beginning to feel accustomed to my grief.   It’s not that life is any easier or that the pain of our loss is any less sharp.    It’s just that I know that pain better and my grief is not such a hostile companion.

What I am also beginning to understand is that we are at the start of a new journey with and without Josh.    And for this I am deeply grateful to our friend Fiona Rodman, a psychotherapist and very wise woman.  The following is an attempt to synthesize some of her ideas as contained in her recent thesis – “Mourning and Transformation – Sifting for Gold.â€Â (MA University of Middlesex)

Sifting for Gold

After I had read Fiona’s thesis for the first time, I had a real sense of a burden lessened; that the grief I had felt for Josh was less complicated and more natural than I had previously supposed it to be.     Here was an account of the mourning process, told not just from a theoretical perspective, but illuminated with the real insight from her own personal experience.   Fiona’s mother died at an early age, she endured the break up of a long marriage, and witnessed her father lose his own battle to dementia.       Her journey – her different journeys of coming to terms with these deaths inform her conclusions of what it means to mourn.

To a certain extent I think I have been caught up with what I thought society had expected of me in dealing with Josh’s death… how to behave, what to say, what to feel.   How could it be otherwise.  Even in this modern age with its fast changing moral and ethical codes, we are so influenced by long standing attitudes to death and its aftermath, that it seems the only the right thing to do is to rely on the consensus and on traditional ideas when we are trying to find a way forward on the journey through grief.    In her essay Fiona, explores the connections and the tensions between personal emotions and public expectations.   What I’d like to do here is to try to extract from this necessarily lengthy and rigorously academic piece of work, some of her basic ideas that have helped me understand a little more some of the thoughts and feelings we have all been experiencing since Josh died.

“Sifting for Gold†is concerned with the transformative power of grief.      Another’s death, particular someone who is close to us and some one we love, is always a life changing event.  This might seem so obvious, it shouldn’t need saying, but until Josh died I hadn’t fully understood how difficult it is for many people to accept this change.    Fear of our own mortality certainly kicks in; confronted with the fact of another’s death, or another person’s loss, our thoughts about the inevitability of our own death become so uncomfortable, they prevent us from truly seeing, or at least acknowledging another’s pain.       As a family, we have all experienced having to skirt round the issue of Joshua’s death, for the sake of not embarrassing a friend or an acquaintance.     Yes, its weird, but to hide one’s own feelings for the sake of another’s shame is, I have found, a common occurrence.       All too often, we hear that people just don’t know what to say, but this becomes understandable when you realise that it’s not just that another’s death is such an ominous reminder, but that the bereaved have indeed undergone a fundamental change.     How that change is managed (or not) is the subject of Fiona’s essay.

Her own mother passed away when Fiona was in her early twenties.   But, it wasn’t until many years later that she discovered that she had not properly mourned her mother’s death.   At the time she had felt dislocated and adrift and that there were deep constraints on sharing her feelings with her immediate family.  “We were closeâ€, she writes, “as if clinging on to a shipwreck together. We could not however, weep together, fall apart, sob and hold each other.â€Â    Her father although loving and loyal, belonged to a generation that had known many war deaths; they were the survivors who had been severely traumatized by the horrors of war but who had learnt to suppress open expression of grief.    “Laugh†he would say “and the world laughs with you; cry and you cry aloneâ€.   Fiona is only now aware of how this view had shaped her own emotional responses, leaving her feeling alone in a world where “the role of tears as communication is completely denied.â€

The standard model of grieving in 20th century Britain relies heavily on the stoic – our way of doing things has been to keep a lid on our emotions, to be strong and to weep only in private, and to avoid any public display of frailty or despair.   And the advice is to put some kind of time frame on the business of processing loss and to find closure – after Josh died a close friend even counseled that to avoid becoming excessively morbid, we would eventually have to ‘forget’ Josh.     The idea is that sooner or later we must ‘move on’ in order to regain the composure and the equilibrium necessary to continue with the rest of our lives.   To do otherwise is to risk a pathological descent into melancholia and depression and the social exclusion that will inevitably follow.

Death of course is all around us – over 10,000 people die every day in the UK, yet for most of us contact with death is relatively rare and as individuals many us lack the experience as well as the social models to help us deal with grief and those that mourn.     And when death happens unexpectedly many of us are understandably but sadly ill equipped to handle the emotions that ensue.   “We don’t learn to mourn at our mother’s knee†observes Su Chard in our film ‘Beyond Goodbye’ (Su is the celebrant who conducted Josh’s funeral.)     Conflicting feelings of sadness, despair, confusion, anger and guilt, which I’m sure all who knew Josh, will be familiar, need to find expression.       But if the emotional climate of society is such that we show only those emotions deemed appropriate for the occasion then what will happen to the inner rage, the impulse to self-destruct, and high levels of anxiety, ambivalence or even the manic laughter that can overcome us from time to time.  Not being able to mourn her mother Fiona writes of being exposed to terrible and “unlived emotional states.â€Â   Her experience of loss and separation were never really resolved but continued to provoke, “turbulent unintegrated long fingers of pain…that seemed to clamp my heart and block the flow of my beingâ€.

I was faced with a similar ‘block’ when aged 21 (a year younger than Josh) I too was involved in a road accident.   I was on holiday with my girlfriend in the former Yugoslavia, when the car we were traveling in was hit by another, ran off then road and fell into a deep and fast flowing river.   My girlfriend, Gillian could not swim.   She died.  I survived.      Totally unfamiliar with very unexpected feelings (particularly guilt and shame) and without the necessary understanding from friends or family, (and without professional help) I too now understand that I was unable to process my grief in a particularly healthy way.    Much of this really was the isolation that I experienced.   Returning to London, I felt shunned by many of my friends who had their own fears of how to behave, as well as my parents need to protect me from extremes of emotions.      This left me in a place where I felt completely disconnected both from my girlfriend Gillian, as well as from my environment.     At the time I would have seen this as distressing but acceptable, and my attempts to brave my way through it as honorable – the thing to do was to make the best out of a shit situation and to move on.     I had the rest of my life to get on with and to allow a tragedy such as this to mark me felt like failure.     But I had been marked and I had been changed.     And without the adequate means both personally and socially to express my feelings and with no acknowledgement of the importance of the grieving journey, I think I became quite introspective, learning how to cope on my own, actively avoiding close emotional involvement.   I lost contact with Gillian’s family and to a degree I lost my way in life.

But does surviving such untimely tragedies or even the anticipated death of a parent have to be such a lonely experience.     In retrospect Fiona identified a sense of an “arrested capacity to mourn†in the years following her mother’s death.     This led her to explore just what it is within the cultural and psychological life of our society that determines they way we grieve and how mourning has been understood by academics, writers as well as the bereaved themselves.     And going all the way back to Freud she discovers that, after a death, it is the way that we understand our sense of self in the world that plays a crucial role in our ability to regain the necessary psychological balance and the stability to continue living as functional human beings.  “Self†she posits, can be understood in two different ways – there is the idea of the ‘objective separate mind’ and the idea of the ‘subjective interconnected mind’.     The first of these philosophical positions, the idea of the self as a separate finite entity underscores a very western view that we are each (at our core) unique and autonomous individuals existing alongside other individuals in a highly individualistic society.      When it comes to processing trauma, of which grief and mourning come high on the list, our way of dealing with it is necessarily an internal and private journey of gradually loosening our attachment to our lost loved one until equilibrium is restored.    It’s a finite (even measurable) process which if unbounded becomes pathological – basically you’re sick if you grieve too long.

Contrast this with more contemporary yet still relatively unfamiliar philosophical ideas which shift the emphasis away from the ‘isolated’ self and the separate mind to a more relationally embedded model of the self, in which mourning and recovery are seen as being facilitated or impeded more or less in response to and with the help of others.   Searching out and recording the experiences of fellow travelers in grief, Fiona findings were confirmed in two ways.    First, whilst previous wisdom was heavily influenced by the pressure to get over it and move on, these new ideas revealed mourning to be a two-fold process with a constant oscillation between deep sadness and attempts to reconstruct life.    Now, as I write this, I believe I am in recovery mode.  An hour ago I was experiencing one of those painfully raw moments of missing Josh.   Later the hurt will return.

The second of Fiona’s findings was that processing trauma is not best achieved in isolation – Fiona writes, “we need others deeply alongside us in our mourning, we need to be known.â€Â  Rather than a private, closed, exclusively personal experience, mourning is here seen as an inter-relational process in which dependency on others is vital for us to heal our fractured life, reassert our sense of self and our ongoing being.

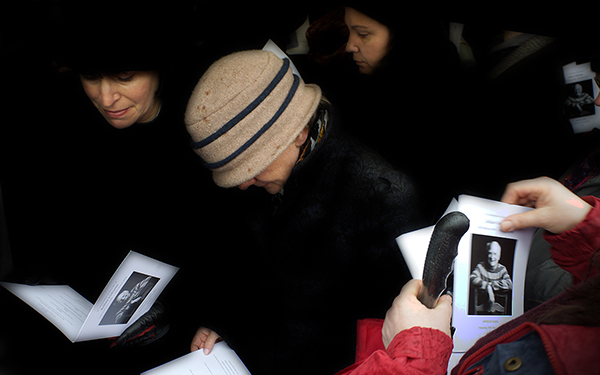

It might seem obvious that to share one’s loss and be supported by others can only be of value to the bereaved, but the actual process of mourning extends way beyond any public ritual in which an open (but limited) form of grieving is found acceptable.  The funeral, that necessary rite of passage, has more often been seen as providing opportunity for a final farewell, part of a closure rather than the start of a journey through grief.

Many people found that our funeral for Josh was not only deeply moving, but it was also quite unique with its emphasis on creating a symbolic journey in which we carried his casket into the main room at the Matara Centre, on to the next and then out into the night.    But if it was remarkable, maybe that’s only because in this country we seem to have lost the idea of a collectivised ritual and its ability to engage in or invent symbolic acts that give meaning to the loss the community is feeling and to the possibilities for healing.

In ‘Sifting for Goldâ€, Fiona describes her visit to the Musee Branly in Paris (“not like walking into a museum but a prayerâ€) in which displays of mourning rituals from all over the globe included ceremonial objects that marked death and its journey as being important as much for the mourners as for the deceased; like the carved wooden boat inlaid with mother of pearl, in which the bones of the deceased were finally sent out to sea after the long community ritual.

What is important here is the way a traditional community will come together and create elaborate rituals, in some cases lasting for years, in order not only to register the loss and its impact, but to help construct a voyage to a different relationship with the deceased.    As we know in many traditional cultures, the dead remain as valuable spiritual guides for the living.

Our family was hugely supported by our local community in organizing Josh’s funeral and their creative involvement deepens the sense of a shared loss as well as providing the impetus for building a new relationship with Joshua.  The viral candle lighting ceremony was highly symbolic of the way we had all been in some way influenced by Josh and could share that with others.

But creating this ritualized journey, (as old as time itself) and the possibilities that holds for a communal sense of loss is not so possible in a world where the individual, the lonely and the private self is the norm.

This brings us back to Fiona’s definition of self, of how we see ourselves, our “selfâ€.  Are we unique, separate identities or part of a continuum with the rest of humanity.      In both cases of course we need to relate to others, but within the model that Fiona describes as the intrapsychic or separated self, we can survive without the other in the belief that nothing of our own self has been actually lost.   Not only that, we can endure the loss knowing that our mourning will be a finite process with a final letting go signaling a healthy outcome to our grieving journey.

However if our view of who we are is based on the idea of our “selves†being part of a commonality of all human experience, (a sense that we all more alike than different) and that we exist as relational beings, then when someone close to us dies, we feel that death as a loss of part of our own ‘self’.  I suspect that all those who knew Josh, all those who had any kind of relationship with him, will accept that when he died something inside of them died as well.

CONTINUING THE BOND

Fiona describes the traditional approach to mourning as “a cutting off and a moving onâ€.   But this need to detach oneself from the deceased has obscured another aspect of the work of mourning – to repair the disruption to the relationship we had (have) with the deceased.

Fiona describes the anxiety and the rawness at the loss of her mother, remembering in detail her illness and her death as if it were yesterday.   “At the same time I could not remember at all.   Such was the pain of bringing her into mind that I could not draw on a sense of continuing relationship with her inside me.â€Â        Twenty years on and in the light of subsequent losses, Fiona identifies this “continuing relationship†with the deceased as key to regaining the confidence and the stability we need to carry on living, to carry on living with another’s death.   She draws on the ideas of psychoanalyst, Darian Leader, that “we need to separate out the loss of the other from the loss of what we mean to them, the person that we were in their eyesâ€.

That last phrase “the person that we were in their eyesâ€.     Eyes that no longer see; the person that we were and are no more.     We lost Josh and what he meant to us, but we also lost that part of us that was Josh and what we meant to him.   Fiona desperately misses being a daughter to her mother, “of mattering to her†and I have not only lost a son I have lost my role as a father to that son.     No longer can I advise and argue with him, no longer can I protect and admire him, no more long phone calls to gather up his news, no more am I his last port of call.

With Joshua’s death we are changed and as much as we need to come to terms with his, or any death we need to acknowledge our changed selves, something I was not aware of when my girlfriend died all those years ago.

Fiona cites the work of The Compassionate Friends, a self help group that supports parents who have lost their children.   By meeting regularly, mourners are encouraged to name and speak of their child and to hold rituals on important dates.     Memories of the child and the parent’s grief are in this way validated and held in mutual recognition.    “Through this shared space†Fiona writes, “a transformation is facilitated in which the child comes to occupy a different, still living, inside space.    The pain that the child is dead and will never again be present in the way that it was, is given room to be, but through a shared space and over time this other internal journey can take place.â€

As I read these lines I wondered how this could be possible.     With only memories and history to sustain us, with no actual Josh, how could a new living relationship grow inside of me?      Then I was reminded of the various creative acts we have done in order to continue our bond with Joshua – the tree planted on a farm where Josh and his friends would often gather, has now become a Mecca for those same friends and family alike, the photographs I have made since he died, the film we produced as a celebration of his life, this website, all are sustenance for our new relationship with him.   And they are all necessarily shared and communicative experiences – on Josh’s still active Facebook page we talk to him (Josh we talk to YOU) and in speaking of Josh in these varied ways we acknowledge that new relationship not only with him but with each other.

In not relinquishing, in not cutting off from Josh we are in Fiona’s words “reshaping and continuing the bond in a different way, a way that is not a denial that the relationship has changed forever, but a way that honours the place and the significance of the deceased in ongoing life.â€

That our ongoing lives have been transformed by Josh death is beyond dispute. Fiona’s conclusion is that it will be the deep inner work of reframing our “self†in relation to others that will make them worthwhile once more.

The title of Fiona’s essay comes from a line she found in one of Alice Walker’s poems – ‘now I understand that grief, emotional speaking, is the same as gold…’ Yes, there are special treasures to be found in our mourning and grief can be good.

I miss you Josh

Your Dad, Jimmy (July 2012)

Fiona Rodman is a psychotherapist and lives near Stroud in Gloucestershire.     She is currently working on her next book – a further exploration of contemporary practices in mourning and grief.  To read “Mourning and Transformation – Sifting for Gold†in full please contact Fiona directly – mailto:fionarodman@gmail.com

I am particularly interested to find out how any of Fiona’s ideas might resonate with your own experiences – please leave any comments in the box below

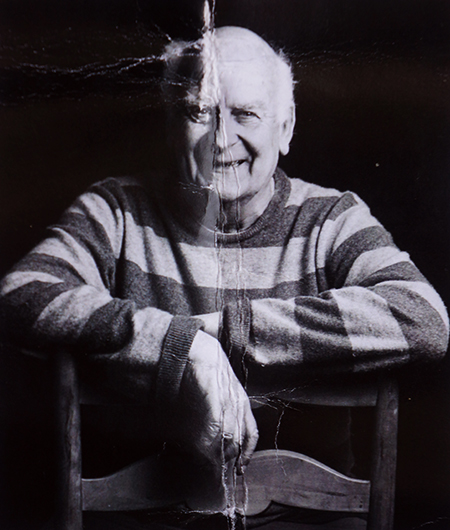

Above – the photograph Josh used for his business card

Above – the photograph Josh used for his business card