Dear Josh,

We’ve done it.  We’ve been to Vu Quang where you died in the middle of the road.   It feels nearly as hard to say that as when we first heard the news of your death. But it is real, just as your death is real so we really have been to see the place where you died and to meet some of the people who were there at the time.   In a sense these are the facts, what we make of them, how we remember them, what stories we tell around them and where we put them in the timescale of our own lives is another matter.

Our day began on the morning after the night train from Hoi An to Vinh.  Actually this final part of our ‘pilgrimage’ to see where you took your last breath really started as we boarded the train with that sense that here we are at last; after more than two years we will soon be connecting with you in a way that we never wished we’d have to.

The train is cramped, crowded and noisy and we get very little sleep but as the morning light comes up, we now know that we are in Ha Tinh province, up until now only a name on a map, a name in a police report.  We are glued to the window as the countryside lumbers past, spellbound by the sheer number of lotus flowers and paddy fields all with peasants in conical hats working the land.  Our first opportunity to soak up the atmosphere of rural Vietnam.

Next door to us is a family of 10 happily cramped in to their tiny compartment. Their two youngest boys have spent much of the journey (irritatingly and charmingly) tapping on our window and pressing their noses against the glass and then running off down the corridor chasing a tennis ball. Squeezing past them is the steward and his trolley offering up rice and soup for breakfast which we decline politely. The last time we were on such a sleeper we were on our way to Italy. You were eight and Rosa was three. We were going to  spend a week with Sam and Doone and their Mum Adrienne. Remember the dead snake they were so keen to show us as soon as we arrived. To feel you so close yet to know you couldn’t be further away is so hard. and we wish with all our heart we could hug you one last time.

Next door to us is a family of 10 happily cramped in to their tiny compartment. Their two youngest boys have spent much of the journey (irritatingly and charmingly) tapping on our window and pressing their noses against the glass and then running off down the corridor chasing a tennis ball. Squeezing past them is the steward and his trolley offering up rice and soup for breakfast which we decline politely. The last time we were on such a sleeper we were on our way to Italy. You were eight and Rosa was three. We were going to  spend a week with Sam and Doone and their Mum Adrienne. Remember the dead snake they were so keen to show us as soon as we arrived. To feel you so close yet to know you couldn’t be further away is so hard. and we wish with all our heart we could hug you one last time.

We are met at Vinh railway station by Uoc, the Vietnamese secondary school teacher who helped your friends after the accident.  He is one of very few fluent English speakers in this remote part of Vietnam. Josh, we want you know this about Uoc; he is a complete LEG-END. One of the kindest, most thoughtful people we have ever met. Before our trip, and when first we contacted the British Embassy in Hanoi we asked how we could find the man who was called out from his class to translate and help with the police reports. We received an email almost by return from Uoc himself – it was as if he’d been waiting for us to find him.  Now as we step of the train (which is running nearly and hour late) he is there to greet us.  He has spotted us immediately (mind you, we are pretty easy to identify as the only white people on the platform) and guides us to a food stall under some trees near the taxi rank. Uoc has the look of a young boy, with wide eyes that are hungry for knowledge and as we sit drinking sweet cold sugar cane juice, he begins to tell us what happened when he arrived at the scene of your accident. But it is all too much too soon. We have only just stepped off the train and we need to adjust a little more to being in the presence of the man who would’ve seen your body lying in the road. The enormity of what lies ahead for us, is, we realize, only now beginning to sink in.

We arrive at Uoc’s home town Huong Son after a two hour dusty car ride through countryside that we imagine you too would have been familiar with.   Not that many cars on the road but so many motorbikes, so many trucks and buses, all with horns blaring, weaving through potholes, overtaking, undertaking, this side, which side of the road, all avoiding each other and all surviving, all somehow staying alive to do the same tomorrow.   It is midday and Uoc takes us for lunch. Huong Son is not the sort of place for restaurant so you get and you eat what you’re given. Soup, noodles, pigs foot, some spring rolls (as you will know you get spring rolls of varying quality everywhere in Vietnam) and some strange pickled berry things that are common fare for the indigenous peoples from the hills not far from here – (not that nice!)

Huong Son buzzes with life but it is far from the tourist trail and the rooms in the hotel Uoc has booked for us are dark and decrepid; a Turkish jail would have more charm. Very basic really, particularly after the luxury of  the house in Hoi An but again the sort of place you would’ve taken it in your stride – (note to selves – must look up that footage you took of deciding who should get the beds by playing paper/rock/scissors – you lost we think).  But Uoc has planned everything for us with real sensitivity and he wants us to be fully rested before he takes us to Vu Quang.  Jimmy and Joe doze, Jane stays awake.  It is late afternoon when Uoc comes back to collect us.

Vu Quang and the moment on Ho Chi Minh highway where you swerved to avoid an old man walking his bike up the hill, is a short half hour journey away. Â In the car with us are Uoc, his sister and his two year old baby daughter Sami who bounces around between front and back seat. There is something normalising about them being there. For them just another ordinary day out. Rosa points out Vietnam is so spiritual there is room for both life and death here.

We are now traveling down the same road you and your friends were on two years ago and we can all sense the exhilaration and the real fun you would be having on your motorbikes as the countryside, this beautiful countryside sped past. The road rises and falls over a gently undulating landscape of forest and farmland both meeting the roadside as abruptly as past meeting the present.  The driver narrowly misses a water buffalo which has decided to resist its owners attempts to prevent it taking a shit in the middle of the highway.

A mile or so later we begin to recognize the landscape from the photos of the area we have seen on Google Maps. The road divides into a dual carriage way and the line of lampposts on the central island stretch into the distance. The driver slows and pulls over to the side as we approach what looks like a roadside police check and our first thought is we have been booked for speeding. But Uoc has arranged for us to meet the cop who attended the scene of your accident. This is amazing. Uoc really has thought of everything to make this journey of ours as meaningful as possible. The policeman looks at Joe and then at Rosa saying they must be your brother and sister as they look so much like you.  He then follows on his bike and a couple of miles later we again pull over to the side.

We are here. The heat blasts us as we step out of the car. (All new cars in Vietnam have air-con – but we guess you know that!) It’s like walking into a wall of solid hot air but we also have a very real sense that we are stepping through a curtain of time, to a place where time itself no longer has the power to order our lives. The early evening sun throws long shadows as we clamber out onto the tarmac. We are a now family of five again, together in spirit and bound by love and our completeness spreads out across the hard gritty surface with an unexpected and soothing calm. Here at the place of your death we can feel the chains of mourning beginning to loosen just a little. At first there is nothing to say. Then our wondering becomes wandering and silently we begin to explore the scene, each our own archeologist superimposing previous imaginings onto this very real, this very actual roadside .   When did we-five become we-four?  How did five become four? Why, oh why did we lose you?  In some ways we already know the answers to these questions so what we learn here is confirmation not of the facts of your death but a sort of joining together of our own stories – stories that were ‘then’ becoming much more stories that are ‘now’, and stories we can now perhaps stitch together into the fabric of what has to be – our lives continuing on while yours does not.

A constant stream of dumper trucks labours up the hill from the nearby quarry.  Past them and on either side flow motorbikes with a variety of loads, hay bales, water canisters, mattresses.  Did you see them like we see them now? A farmer harnesses an ox to his cart and leads it across the road oblivious of the traffic. Did you notice him? Somewhere behind a gateway a dog barks.  Did you hear it? And did you see, did you sense, were you aware of the people rushing to the roadside as you fell?  Because Josh, just as two years ago when they came to witness something out of the ordinary on this unremarkable stretch of the Ho Chi Minh Highway, so now they are gathering to watch and observe us, a party of Europeans with their cameras and their sunburn and their somber looks. There seems to be  something vaguely amusing in this spectacle until Uoc explains our presence. He thinks he has discovered someone who actually saw your accident: someone who then explains at length the events of that day. The crowd assembles while we wait for the translation, but it turns out he is only a friend of the person who saw it.  As would happen anywhere, everybody wants a piece of the action,  a claim on the tale to be told; especially when death is one of the players. This is of no consequence. It is clear that all the stories of that terrible day do tally and we are content just hear the sound of voices and be in the presence of strangers that have also been marked by your death.

And Josh, they have been marked and they do remember.   On 16th January each year since, a small shrine appears by this roadside. Wherever we have gone in Vietnam, people remember their dead by bringing offerings, (you will like this Josh) of sweets, beer, chocolates, fruit and cake! – and of course incense. Uoc says he too comes here on that day bringing as he does today a box of cakes. We begin to prepare our own shrine for you. We have brought a few momentos; some photos, one of your business cards, a Ministry of Sound CD, a card from the Gales, a string of shells that Hollie and Charlie have made. One of the villagers runs over with an old yogurt pot filled with sand. This is to place our incense sticks and at first he wants to put it in the middle of the road, on the actual spot where you lost your life. Others are walking out into the highway to debate the point. Is it here, no more likely it is there, perhaps it was here; we can see them becoming quite troubled in their need to get it right.  Would you know, would you care?

In the end we call them back to the verge and the yogurt pot finds what feels like its rightful place under the safety barrier. Uoc leads our little ritual and lights the incense sticks which we take turns to set in the sand. This is our biggest moment and it is not without tears –  and a long, long group hug. In the purest and simplest way possible we are honouring you and we are remembering you with a small ceremony that is and will remain as important to us as your funeral.   But this time we are borrowing from another culture and another set of beliefs where people are expected to live on, to be reincarnated, where karma is of utmost importance to life and death, and where the spirit of ones ancestors have a sacred place at the heart of every home to be looked after and revered for all time.  80% of Vietnamese are Buddhists and practicing or not there isn’t a house in this country where the first thing you see as you enter is a shrine to the departed.

But this time we are borrowing from another culture and another set of beliefs where people are expected to live on, to be reincarnated, where karma is of utmost importance to life and death, and where the spirit of ones ancestors have a sacred place at the heart of every home to be looked after and revered for all time.  80% of Vietnamese are Buddhists and practicing or not there isn’t a house in this country where the first thing you see as you enter is a shrine to the departed.

Uoc, his sister, and 2 year old and the policeman are squatting by the roadside. They are watching Joe as he ties some Tibetan prayer flags onto a lamppost (another gift from the Gales). Below it he scratches your name. Rosa scratches a kiss.  Uoc promises that he will continue to come here every year on January 16th – and we believe him – absolutely.  ‘This is’ he says ‘your day of the dead’. We are not Buddhists and we don’t believe in life after death, but what we did last Monday was deeply affecting.  We will carry this moment and make it part of our goodbye to you… our forever.

With so much love

Mum and Dad

Ps – later that evening Uoc invited us around to his house for dinner. Â Afterwards some of his students came round eager to practice their English. Â Joe was more than happy to oblige with an impromptu evening class.

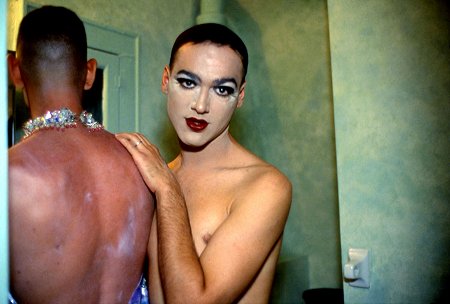

Above – the photograph Josh used for his business card

Above – the photograph Josh used for his business card