The following is our report on a photography workshop Jane and I ran at the TCF National Gathering earlier this year – apologies if this appears a little late but life work and other things do tend sometimes to take over from our tasks of keeping you informed of all the things that have happened since Josh died.   In any case time for us doesn’t really feel like a series of moments that gradually disappear into the ether,  or off the bottom of a blogroll, so we hope that this account will be as relevant to you in a years time as it does now.

Saturday 11th October  2014 …  it’s the annual Gathering of The Compassionate Friends and Jane and I have an opportunity to share our joint skills in photography and therapy.  We are running a photography workshop for bereaved parents and siblings – EXPLORING GRIEF WITH PHOTOGRAPHY.   Our two disciplines seem to gell together seemlessly and the first part of the course is going well – the participants have split into groups and and are sharing the photos they have brought along.  We have a good turnout – two 90 minute sessions both completely full – most with very little practical experience of making photographs but all with a huge amount of stories and memories to share.  The room is buzzing with emotion.   Both therapy and photography are ways in which to seek beyond the surface layers and discover hidden emotions.   And while photography can have a more tangible result they are both very much processes in which everyday realities can be tested and revealed anew.  At least this was the approach we hoped to explore in the new photography course we have devised and for which this is its first outing.

The Compassionate Friends is a charity we have now become quite closely involved in and attached to. TCF is important to us, not just because of the video we produced for them (SAY THEIR NAME) but because it truly is a peer to peer network run by and for bereaved parents.  Not only do we share our grief (it makes life so much easier when we do) we can also share our skills and for us this represented a very special opportunity to contribute something of our own to a community that had, I suspect, not given much thought to the potential of photography as a therapeutic tool, especially for the bereaved.

So how do we and how can we use photographs to help us as we grieve?    Both the photos that we already have of our child and the ones we intend still to take.   We asked everyone who signed up to the sessions to bring along at least three photos of their child, pictures that have a particular resonance or evoke a special memory.  Further into the session we will be asking them to choose just the one picture in order to ‘reframe’ it in a way that will bring it more into the present.  Our purpose here is to experiment with ways in which we can keeping an on going relationship with our child by employing one of memory’s most valuable assistants – the photographic image.

In preparing the course, I began by looking for some good examples of what others had done in this area.  As Josh’s sister Rosa has pointed out in her article (Making it Real – Death and Photography)  every photo we take will outlive its subject and as such has enormous potential to transcend  that final moment between life and death, a fact well recognised by artists and photographers ever since the medium was discovered 200 years ago.   But by  googling  a combinations of various words; GRIEF, PHOTOGRAPHY, DEATH, BEREAVEMENT etc, I found little that spoke to my own experience of life since Josh died.    Beautiful photographs as they are, mostly they seem to fall into high art or reportage, neither of which seem to be of much use to anyone looking to express their own very personal feelings in the days months and years following the death of a child.

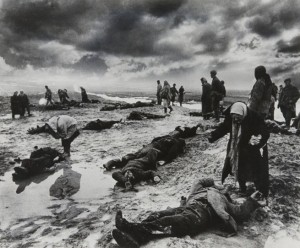

Typical would be this photo of grieving parents following an earthquake in China.  Although as a press photo it has the potential for a sort of anonymous association for the viewer (we can feel their pain)  it does little, I suspect, to help the mum and dad who have just lost their daughter.  Why?  Well I think its because they haven’t been involved in the real work of taking the photograph.  Did they know the photograph was being taken or did they pose suitably grief stricken in the rubble, their daughters image conveniently arranged so that the world can see her in full view.  Whichever,  this is an image of tragedy for public consumption and feeds a very common place idea of what grief should look like but, buried as it is in the historicity of the moment it can never convey what grief really feels like as one of life’s longest lasting experiences.

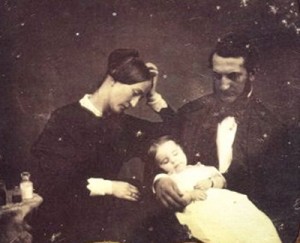

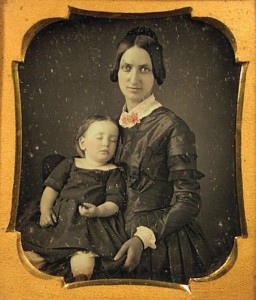

A little closer to home (in the sense of a personalised photography) I found this remarkable website NILMDTS – Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep – a sort of photo agency that will record for you a moment with your child who has died at birth.   This is a free professional service and is in the tradition of post-mortem very popular in the States at the  end of the 19th century, a time when child death in the family was commonplace, though we can assume no less traumatising..

Now as then these  photographs carry a huge emotional charge both for the bereaved families and for us strangers looking on.  Unlike a press photograph and in common with all portraits they have demanded the active participation of the sitters.  Mother has taken her dead baby in her arms and posed specifically for the camera.  She is performing a drama with the shortest of stories but one which will have lasting impact and as such has the potential for huge therapeutic effect.  The moment is both real physically and emotionally and she is in effect taking the first step in a life’s work of continuing her bond with her child.  This is a lasting image that has captured a hugely significant moment and one in which she can return to time and  again as she remembers and try to construct what (or who) might have been.  But again, as artefact, these post-mortem pictures are and can only be,  locked into the past, even while they generate very current as well as very healing memories and emotions.

It was with these thoughts in mind, that we began our workshops  with an invitation to explore  ways in which we can use photography to generate a continually evolving set of stories and impressions following the death our child. We had each of us brought favorite photos and were now explaining the  stories behind them and the memories they evoked. In the small groups we had formed words spilled out and across the room in a veritable hubbub, a cacophony even of voices all (and I think this is the really interesting bit) trying to describe their feelings, all trying to convey their emotions.  But at the same time the mere act of vocalising our thoughts, of telling the narrative seem to get in the way of really connecting with these photos and the child within.  In a sense words were failing us.

At this point then we asked people to remain in groups but to sit quietly and merely observe their images, together and in silence.  In the hush that followed Jane used her ‘mindfulness’ techniques, encouraging us to stay in the moment however difficult the feelings, to try and lose a sense of time and to find a connection with our child that is now and something more than just memory. It was extraordinary, as the words disappeared and the emotions took over, hands felt for another to hold, an arm went around another’s shoulder,  tears began to form and frankly, I was stunned.

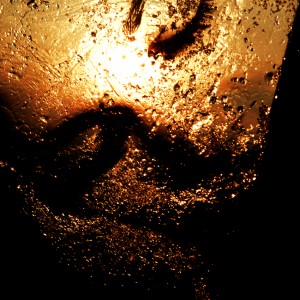

Photographs of course are always memories – they are always of the past; of something that has already happened.  You cannot take a photo of the future.  But while they are always of the past, they are also always in the present. And like memory their meaning or the meaning they have for us, can evolve with time, sometimes radically and overnight.  We recognised this in the photos we had brought of our children … innocent snapshots that have now become overloaded with longing and painful fantasies of what might have been.   In my book RELEASED I wrote about how an image of Josh taken as part of a series of portraits of people with their eyes closed, had now attained a kind of iconic status in the way in which we remember him – and the way in which we ‘reinvent’ him in a continually shifting process of trying to find meaning in our lives and in his death. Personally, I have found much comfort in being able to re-photograph Josh’s  image – it has taken me from the raw pain of remembering too much to a newer sense of a continued relationship with him.  No longer here and forever dead, Josh still remains a huge presence in my creative endeavour and very much part of my life.

So there are two aspects to this business of exploring grief with photography. There are the photos we already have of our child who is now dead.  Photos that were taken in all innocence of what the future might bring, now portals to our memories holding us close to a life that once was, both ours and theirs.  And there the images that we can now make – post tragedy – of the lives we now inhabit, both ours and theirs (do they not live on within us?).

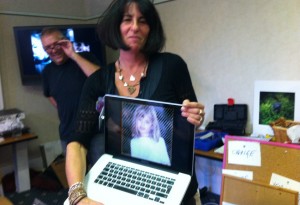

For the second part of our workshop people divided into pairs and together attempted to create a photograph that reflected some of these concerns.  In a way what we were trying to do is to weld together the past and the present – the past with all its longings and the present full of our current desires – and in so doing rebuild our sense of a future.  As all bereaved parents will know, when your child dies, you are immediately thrown into a world in which the future has very little meaning.  But in this act of re photographing our child’s image we began to see some real therapeutic possibilities in the way we can continue our relationship with her/him with less pain.  With the photographs we now made we could forgo the ‘what if’s’ in favour of the ‘might be’s’.  We might even imagine a time when we can look upon their face and smile again and know there are more photos to come many of which we haven’t even dreamed about – yet.

24 people attended our workshops and you can see some of the resulting photographs by clicking on the image below.  Some of the photos remain private so we are only publishing those for which we have permission.

EXPLORE THE RESULTS

Some of the thoughts and feedback about the sessions …

“inspirational – I have been so sad that we have no new photographs of (our child) and now I feel I can put all our pictures into a new context”

” …painful, powerful, beautiful meaningful and extremely well run. Â A perfect combination of professionalism, creativity and empathy”

“looking at my picture of (my child) was so hard … I have always thought I was so totally rubbish at photography and not really interested in it but it has inspired me to do more in the future”

“but maybe the tears are necessary and maybe they feed the creative process ..”

“You have shown us a beautiful & really unique way  to remember our very precious children ….. I thought I would get very upset seeing (my child) on the screen …. but in fact because it was so special, it was actually comforting”

“such a beautiful way to continue our bonds and to make new ‘memories’ with (my child).  Jane and Jimmy, you handled our feelings so sensitively and I feel uplifted”

Jane and I feel very encouraged by this and will be offering a more developed version of EXPLORING GRIEF WITH PHOTOGRAPHY in the future.  In the TCF workshops we were concentrating on re-photographing an already existing image but there so many more ways of photographing our grief.  We also realise that for some  the image of their child still holds too many painful reminders or that they might want to focus on a more abstract sense of their grief.   Grief afterall is such a complex range of emotions that finding words to describe them often seems to result in cliche or just very ordinary and nothing like what we are truly experiencing.

And this is where making new photographs can help to play a part. We can learn to express our thoughts and feelings in a language that is not so literally tied-bound.  By finding the visual metaphors that are in a way unique to us and that express our grief, ours and ours alone, we can interpret our feelings and our experiences in our own way.  In a way this is our route to honesty, something others are bound to recognise.   We may also find that despite the very solidity of a photograph (this did actually happen – this person did actually exist) the language of photography is very fluid, that photos in themselves hold no particular meaning outside of the way they are viewed. But isn’t that a bit like grief anyway – a constant slipping and sliding of feelings and emotions around a central fact – our child has died.

Thanks for reading

Jimmy

December 2014

If you want to know more about our work or would like us to create a course for you please use the CONTACT FORM on this website

Look out for my next photographic series

Another Place Beyond Time – coming soon

LINKS

The Compassionate Friends – WEBSITE

Now I Lay Myself Down to Sleep – NILMDTS

Continuing Bonds – on BEYOND GOODBYE

Rosa’s essay -Â Making it Real – Death and Photography

Jimmy’s book – RELEASED

Above – the photograph Josh used for his business card

Above – the photograph Josh used for his business card