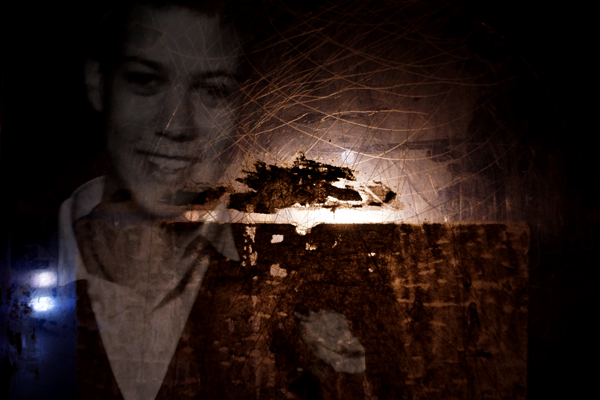

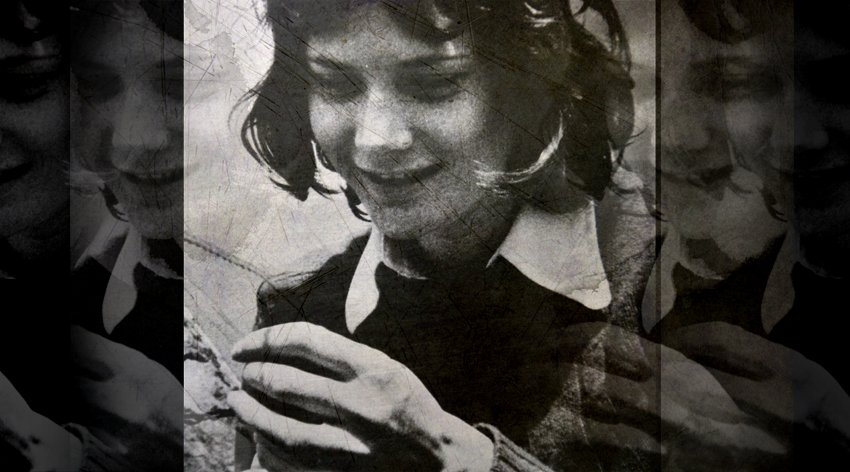

That sleepy picture – the one that Josh used for his business card – the one that has become such a poignant reminder of who Josh was for us. Â We take it everywhere we go and we took it with us to Vietnam and Cambodia.

It’s a photo of Josh pretending to be asleep. Â He is not really asleep, he has closed is eyes on my request and in a sense I am in that picture too. Â You can’t see me but I am there – as a father and as a photographer, two roles, two identities that I cannot imagine being without. Â Â The photo was taken as a joke really. Â I was in the middle of a project taking photographs of people, most of them random strangers I met in the street – but with their eyes closed – and one day, on a rare visit to London, we decided on the spur of the moment to do one of Josh. Â Â We were with his brother Joe having a drink on the South Bank – that is Joes hand Josh is leaning against. Â Â IÂ thought no more of it until Josh turned up a few weeks later showing us the design for his business card with ‘that sleepy picture’ as the background. Â It reminded me of the time many many years ago when my father took some of my photos and made some water colours from them. Â Â I felt as if there could be no nicer a tribute to my skills and the way I like to see the world. Â We all like recognition from a parent, do we not. Â Well ditto in reverse with Josh – I had no idea he thought much at all about my ideas as a photographer (and maybe he didn’t) but to follow them through as a way of promoting his own work (he worked as a video producer for the Ministry of Sound) was very very gratifying.

There is so much in that photograph for me and I could go on for hours about what it meant then and what has come to mean since Josh died.  Of the moment we took it I recall being slightly surprised at how both brothers were happy to join in with my weird ideas.  But I also I remember how little I was seeing of Josh since he moved to London and how I would savour every moment with him; and I remember how much he had matured since he’d left home and how much I valued his easy unhurried attitude to life.  As with all photographs of loved ones who have died there is a terrible tension between that moment of their aliveness at the time the picture was taken and the photographs ability to live on beyond their death as a constant reminder  of their absence. There is both pain and joy co-existing in a way that has no equivalent. Particularly so with this image of a boy pretending sleep, the more poignant now depicting as it does, a young man in perpetual sleep.

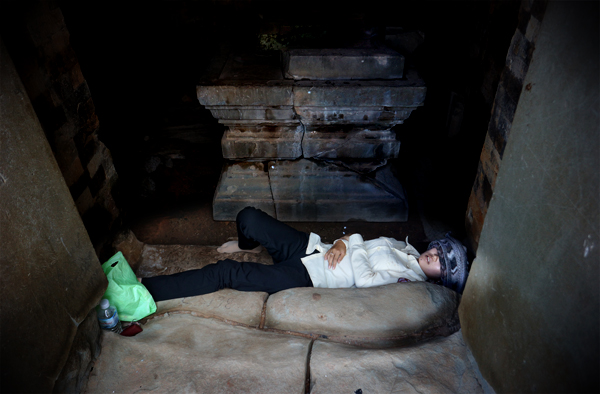

For this and many reasons then, the photograph  now represents a real and continuing bond between the two of us.  Unable now to take any further photographs of Joshua I have reworked it in numerous ways since Josh died  (see this gallery here ) and from time to time, I take it out of my wallet, place it on a hillside or on a gatepost, or simply hold it in view and photograph it.   Somewhere in all this is the idea that if we have a record of Josh on our travels, its proof that we haven’t forgotten him – it is one of the many foolish ways we have of staying in touch with him.

For this and many reasons then, the photograph  now represents a real and continuing bond between the two of us.  Unable now to take any further photographs of Joshua I have reworked it in numerous ways since Josh died  (see this gallery here ) and from time to time, I take it out of my wallet, place it on a hillside or on a gatepost, or simply hold it in view and photograph it.   Somewhere in all this is the idea that if we have a record of Josh on our travels, its proof that we haven’t forgotten him – it is one of the many foolish ways we have of staying in touch with him.

This is Halong Bay, a four hour drive from Hanoi and one of Vietnam’s foremost travel destinations. Â Â We wanted to go there, one because it is an amazing sight, two because you get to stay over night on a luxurious junk, but three because it was one of the places we knew Josh had been. Â Â And we knew he been there because we have the photographs to prove it.

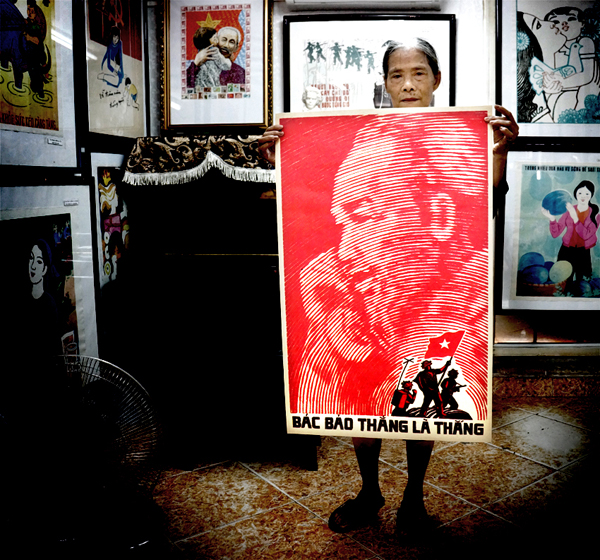

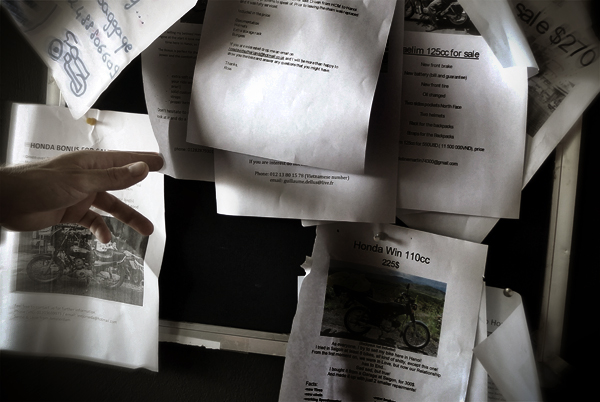

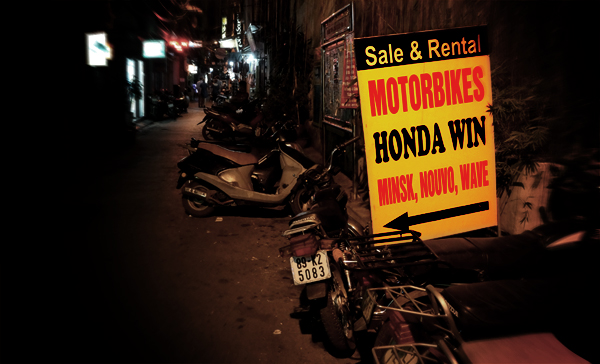

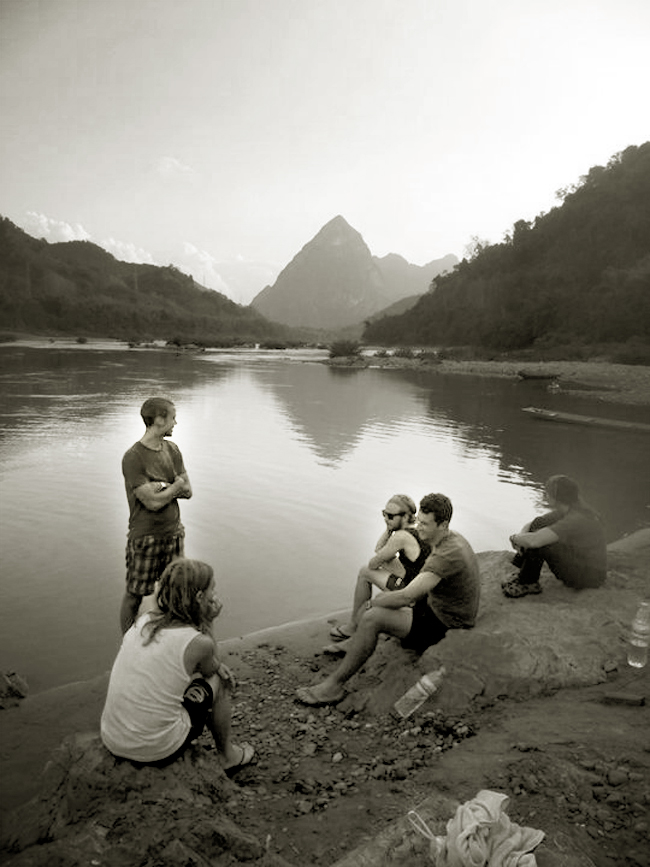

Josh had traveled to South East Asia on his own but had met these young men in Laos and they rendezvoused again in Hanoi making plans to ride south on motor bikes. Â Of the five friends pictured here, Dominique and Don (to Josh’s right) and Jesse (second from right) would be with him at the time of the accident. Â They are the ones who sent us all the photos we have of Josh from his time in Vietnam. Â Â They are the sort of photographs you would expect from a young man traveling the world, meeting new friends, seeing new places, and wanting to send a message back home – here’s me over there, having a brilliant time, I’ll tell you all about it when I get back.

Imagine that we didn’t have a single photograph to remember him by.  Not one. Not even as a baby or a little boy growing up. How would that be?  Would we forget what he looked like?  Did he have short hair or long hair?  Did dimples appear everytime he smiled?  Was that really a man’s beard or still the down of youth?   And without his likeness in a photograph, how long would it be before we forget him altogether?    But even if the power of his likeness is overwhelming, does the fact that these are staged pictures, mean that we might lose too soon the sense of who Josh was rather than what Josh looked like.   We have no pictures of Josh climbing the steps to that viewing platform or lugging his backpack on board the boat.  None of the stuff that would tell us more of how he was possibly feeling.  We have no more than the photographic evidence of his presence in Vietnam and they cannot really tell us how confident he was with these new friends; was he nervous about the bikes they had bought, weren’t they just a bit pissed off with cold and the rain.  He is not here now to tell the stories behind the photos and without his voice there is no anchor to secure what little we do know of his adventures.  He had told us on the phone just how cold the north of Vietnam was in winter time, how pleased he was to buy a replica North Face jacket at half the normal price, but  we must use our own imagination to complete a narrative  of their trip first to Halong Bay and then south on the Ho Chi Minh Highway.

We don’t know how long Josh spent on Halong Bay.  Given the price and the season we suspect his was a day trip.  We were visiting in summer and were able to make slightly more of it  spending one night on the boat, visiting some caves, eating some fine food and diving in for a swim in the rain.  Unlike January when Josh was here, the summer heat is oppressive.  It is also the start of the rainy season and when it rains, it rains.  It rained all night long and into the morning by which time we had had enough floating luxury.

On our return to Hanoi, we decided to mark Josh’s presence there by scattering some of his ashes in Hoan Kiem Lake.   Translated this means The Lake of the Returned Sword after the legend in which the then 14c King was ordered by a holy turtle to return the sword that had helped him defeat the Chinese invaders.   The turtle’s descendent is said still to live in the lake and like (or maybe unlike) the Loch Ness Monster, there have been numerous ‘sightings’. To the north of the lake is a small island on which stands the Ngoc Son Temple connected to the shore by a pretty bridge.  It was here we felt most appropriate to stand again for a moment, to remember Josh, and to feel a little more connected not just to him but also to the Buddhist traditions that are everywhere part of Vietnamese life.  Josh of course was not a Buddhist and nor are we, but being in a country where Buddhism is so strong helped us to understand and to be more comfortable with his death.  Remembering and honouring those who have died is such an ordinary part of everyday life in here, that our little ritual, public as it was, provoked little interest with passers by. It was hard to feel grievous, or even that sad. Such has been the welcome we have received in Vietnam. it wouldn’t be until our return home, that I would again feel the full force of Josh’s death, the sharp ache of my boy’s total and forever absence.

To give our ceremony more substance, we again drew on the power of Josh’s photo. We tore the pictures of him from one of the Order of Ceremonies we had used for his funeral and watched as they drifted down in swirly gig fashion to float on the surface. Â If there had been a current no doubt we would’ve rushed to the other side of the bridge and wait for them to appear as they continued their journey downstream. Â As it was the ripples on the lake gradually softened these shreds of a life, and Joshua’s image slowly sank beneath the surface and disappeared from view. Â At the same time we let his ashes trickle through our fingers and into a slight breeze that had quietly begun to stroke the water.

How many times in the last two and a half years have we said goodbye to Josh?  Somehow it did feel easier this time. Now that we have witnessed the place where he died, I think we are more secure to let him go. Now that we have found a tradition that allows the dead to continue living without embarrassment, we are more comfortable with the pain of our loss. Now that we have scattered a small part of him  in a strange land we are more able to nurture our memories and to construct anew our own special rituals.  And as Josh and his death find their place in  our own family mythology, so perhaps, we can accept them as a more natural part of the human condition, part of that continuum of stories and legends and narratives that we all need in order to make sense of our lives, whatever our culture.

There was,however, no sign of that elusive  turtle.

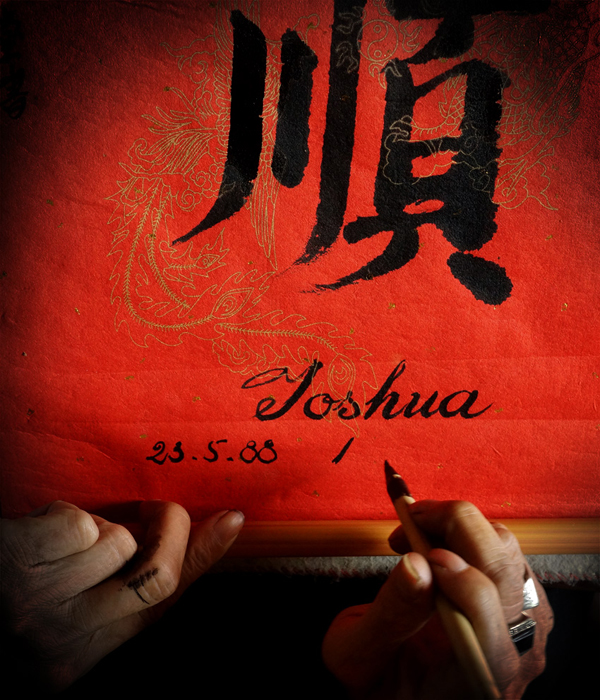

Standing as it does in the centre of Vietnam’s capital city, the Ngoc Son Temple is as much a tourist attraction as it is a religious venue.  And as tourist are, so tourists will be.  Just inside the front door, sat an elderly man earning a living as a scribe; selling his skills to worshippers and visitors alike.   For five dollars we commissioned this beautiful example of calligraphy – we chose the characters with care but I’m afraid I have now forgotten what they mean.

The next day Joe had to fly back home.  Jane, Rosa and I flew to Siem Reap in northern Cambodia. There was of course sadness in our parting as well as a certain anxiety that has become part of the baggage of our family life whenever we, as we must, go our separate ways.  To let go of the sight of each other has and, I suspect, always will be much more of a wrench since Josh died.

The next day Joe had to fly back home.  Jane, Rosa and I flew to Siem Reap in northern Cambodia. There was of course sadness in our parting as well as a certain anxiety that has become part of the baggage of our family life whenever we, as we must, go our separate ways.  To let go of the sight of each other has and, I suspect, always will be much more of a wrench since Josh died.

Josh’s plans once he had traveled through Vietnam, was to continue on to Cambodia, back to Thailand and then on to Nepal.  Our two weeks in Cambodia represented that part of of his trip he was unable to do.  We visited the temples of the Angkor Archaelogical Park and then travelled south to Kampot on the coast and the capital Phnom Penh.  There follows, as a conclusion to this post, a selection of photos of scenes and people we met during our time in Cambodia.   I hope you enjoy them as much as I do.  Since a young boy I have been drawn to the magic of photography.   Hyperreal and pretending veracity it is, I think, the most surreal of artforms.    A photograph has the unique ability to capture life, collapsing it into a single moment, while at the same time casting a spell that will outlive us all.  Photographs can tell big stories and little stories but  always from the past.   A photograph always was, though it alludes to being now.  It can never be the future yet it breathes with possibility.   In a sense then photographs defy time itself and in a sense, you could say that  photography is always in ‘Joshua’ time.

Look in any travel guide for Cambodia and you can see fantastic photographs of the temples of Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom, Bayon etc.  Recognised as one of the seven wonders of the world, they are part of a huge area that was once the centre of the Khmer Republic (9th to 15th c).  This was a period of great prosperity but also of continual change, politically and spiritually, with Buddhism and Hinduism alternating as the predominant  religion.  The ruins are covered with carvings and reliefs depicting various myths, legends and bits of propaganda.  Highly symbolic and full of narrative they read like a storyboard for an epic Hollywood blockbuster and they must have expected to be seen as such.   Not unlike photographs they are still images that have outlived both their makers and their subjects.

As I wandered around the grounds of Baphuon, this butterfly settled on my hand. Â I know many people who would say that this was a little bit of Josh’s spirit visiting me for a while. Â Well maybe, but probably not. Â And actually it matters not because in that moment I could believe that too; for the comfort it brought, Â and the stillness it represented. Â And it hasn’t been the first time I have been seduced into relinquishing my disbelief in some kind of afterlife; Â the tiny green frog that appear at the foot of Josh’s tree on the day we spread his ashes there; the crow that sat and watced as I ate my sandwich in a motorway service area on the M6; Â a white butterfly that accompanied us as we walked to the hill village of Tiglio near Barga in Italy. Â This little butterfly stayed with me for a good half an hour, occasionally flying off to circle around me and land again. Â Long enough for me to take a few snaps so I could share the experience, authenticate it, tell stories about it – to ‘brag’ about it.

As tourists (as opposed to travelers) it is difficult to engage properly with the history we are walking through, but we do love to brag about our visits to historical sites and monuments. Â All the more so now that we can achieve this within an instant. Modern technology has given us license to record our presence ‘in’ history, but often only to the extent that we agree with its potential to make it and us into commodities. Â Â In many ways we have sacrificed who we really are and where we come from, to a generic and ubiquitous ‘facebook’ image that does no justice at all to the moment or the place.

In common with many cultures, I suspect that I have an unconscious wish to believe that Josh is not really dead, merely sleeping – sometimes I can imagine him opening his eyes any moment now, if only to wink at me. Â Â In any case, I have found that my images of people asleep, while the world continues around them, speak to that sense of ambiguity we have between sleep and death.

We are grateful that Josh did not die of hunger or violence, from hatred or in war.  In the late seventies, during the time of the Khmer Rouge, over one million Cambodians including many children did suffer such a fate.  (this actually represents 1 in 8 of the total population).   It was a humbling experience to visit  Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum and Choeung Ek Memorial (one of roughly a hundred ‘killing fields’) near the capital Phnom Penh.   Most haunting are the thousands of photographic portraits that line the walls of the Museum, originally the Tuol Svay Pray High School which was turned into a torture, interrogation and execution centre by hardliners of the Khmer Rouge.   Of the 14,000 people known to have entered only seven have survived.  The vast majority were carefully photographed before being brutally tortured and forced to confess their ‘crimes’.   Inevitably we will draw a comparison between our tragedy (a single personal death) and the horrors of this mass killing.  Not all, but most of these portraits are nameless, their anonymity to a certain extent, protecting us from their real lives, and their real deaths.  This is forensic photography at it’s most clinical but also at it’s most revealing.  Look at that mother and child, she will know they are both soon to die.  And rows upon rows of children and young adults staring forever long past their execution date, maybe the only photographs of them that survive.  See how fortunate we are to have so many photos of our Joshua – particularly the one in which he is feigning sleep.

Cambodia is now a young country. Â 96% of its population is under 60 and only a very few remember the civil war at all. Â The following photographs are the result of mostly very brief encounters. Â As portraits they too hide real identities, though their very anonymity may help us connect to a common humanity in which life and death can be, should be such an ordinary events.

Thank you for reading

Jimmy (July 2013)

USEFUL LINKS

RELEASED (standard version) by Jimmy Edmonds  - for more of my thoughts about that ‘sleepy’ picture see RELEASED the book I published soon after Josh died

Angkor Archaeological Park travel guide – Wikitravel  - for information about Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom

Tuol Sleng | Photographs from Pol Pot’s secret prison (1975-79)Â Â -Â for the photographs from the S21 prison

Killing Fields – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia  -  Wiki page for the Choeung Ek Genocide Memorial