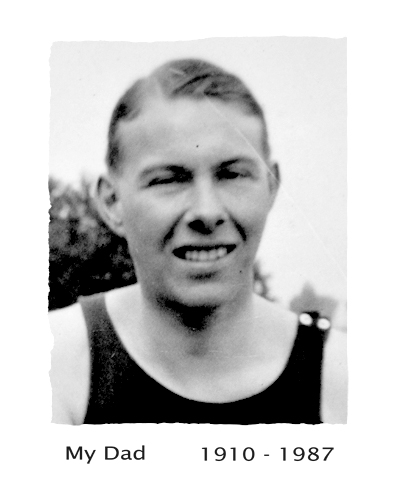

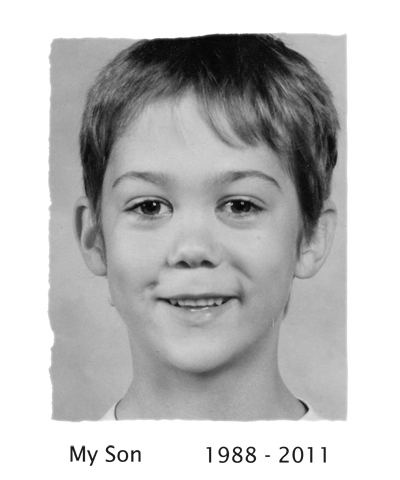

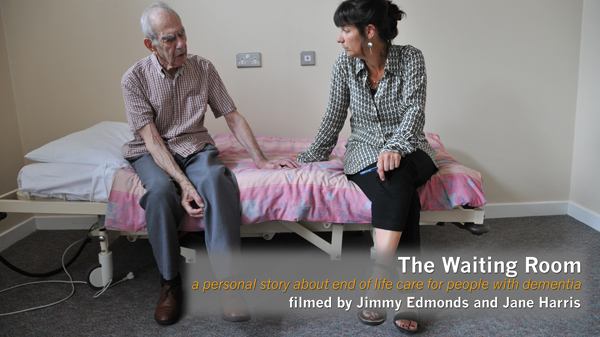

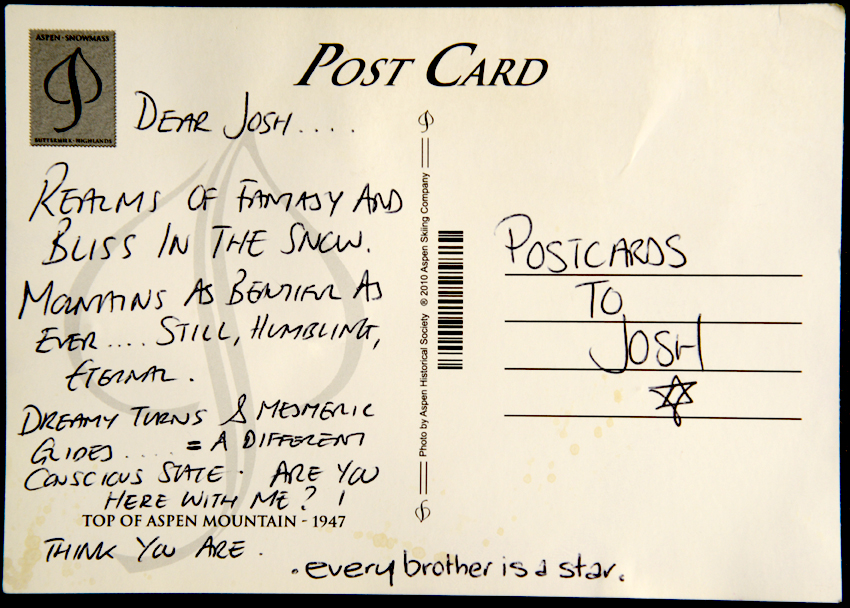

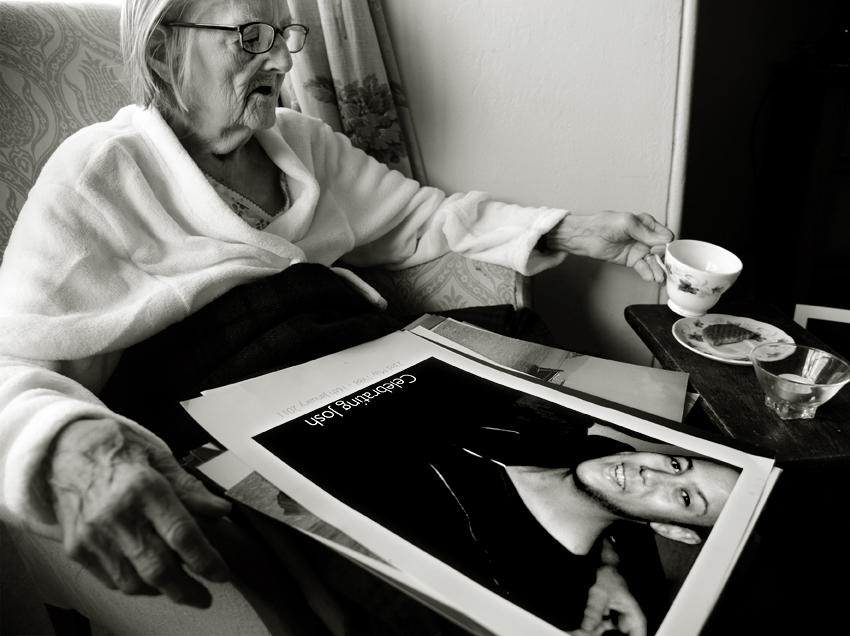

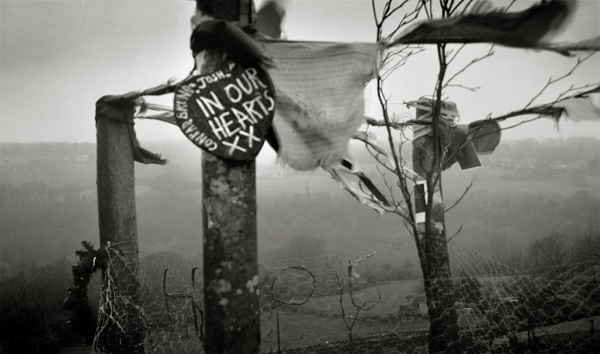

Every now and again, we see or read  things on the internet that express things we’d like to say, but so much better.  Such is this piece.  It’s  by Megan Devine, a mental health therapist who’s partner died five years ago.  So if you’ve ever been flummoxed by how to deal with someone’s grief, caught short on what to say to them, or are just unsure of how to “be'” with them, then here’s a few tips.   I hope it doesn’t sound to trite, but if we ourselves had had some grounding in these ideas in the months (and now years) since Josh died, then maybe we too would have had more compassion for those around us who wanted to help but didn’t know how.   (Jimmy September 2014)

The article first appeared in the Huffington Post in November 2013

How to Help a Grieving Friend

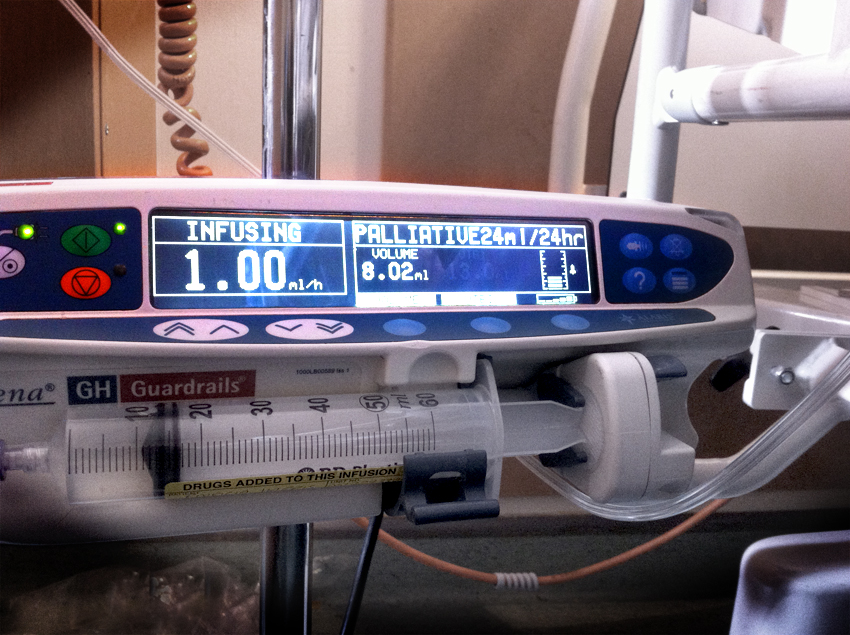

I’ve been a therapist for more than 10 years. I worked in social services for the decade before that. I knew grief. I knew how to handle it in myself, and how to attend to it in others. When my partner drowned on a sunny day in 2009, I learned there was a lot more to grief than I’d known.

Many people truly want to help a friend or family member who is experiencing a severe loss. Words often fail us at times like these, leaving us stammering for the right thing to say. Some people are so afraid to say or do the wrong thing, they choose to do nothing at all. Doing nothing at all is certainly an option, but it’s not often a good one.

While there is no one perfect way to respond or to support someone you care about, here are some good ground rules.

#1 Grief belongs to the griever.

You have a supporting role, not the central role, in your friend’s grief. This may seem like a strange thing to say. So many of the suggestions, advice and “help” given to the griever tells them they should be doing this differently, or feeling differently than they do. Grief is a very personal experience, and belongs entirely to the person experiencing it. You may believe you would do things differently if it had happened to you. We hope you do not get the chance to find out. This grief belongs to your friend: follow his or her lead.

#2 Stay present and state the truth.

It’s tempting to make statements about the past or the future when your friend’s present life holds so much pain. You cannot know what the future will be, for yourself or your friend — it may or may not be better “later.” That your friend’s life was good in the past is not a fair trade for the pain of now. Stay present with your friend, even when the present is full of pain.

It’s also tempting to make generalized statements about the situation in an attempt to soothe your friend. You cannot know that your friend’s loved one “finished their work here,” or that they are in a “better place.” These future-based, omniscient, generalized platitudes aren’t helpful. Stick with the truth: this hurts. I love you. I’m here.

#3 Do not try to fix the unfixable.

Your friend’s loss cannot be fixed or repaired or solved. The pain itself cannot be made better. Please see #2. Do not say anything that tries to fix the unfixable, and you will do just fine. It is an unfathomable relief to have a friend who does not try to take the pain away.

#4 Be willing to witness searing, unbearable pain.

To do #4 while also practicing #3 is very, very hard.

#5 This is not about you.

Being with someone in pain is not easy. You will have things come up — stresses, questions, anger, fear, guilt. Your feelings will likely be hurt. You may feel ignored and unappreciated. Your friend cannot show up for their part of the relationship very well. Please don’t take it personally, and please don’t take it out on them. Please find your own people to lean on at this time — it’s important that you be supported while you support your friend. When in doubt, refer to #1.

#6 Anticipate, don’t ask.

Do not say “Call me if you need anything,” because your friend will not call. Not because they do not need, but because identifying a need, figuring out who might fill that need, and then making a phone call to ask is light years beyond their energy levels, capacity or interest. Instead, make concrete offers: “I will be there at 4 p.m. on Thursday to bring your recycling to the curb,” or “I will stop by each morning on my way to work and give the dog a quick walk.” Be reliable.

#7 Do the recurring things.

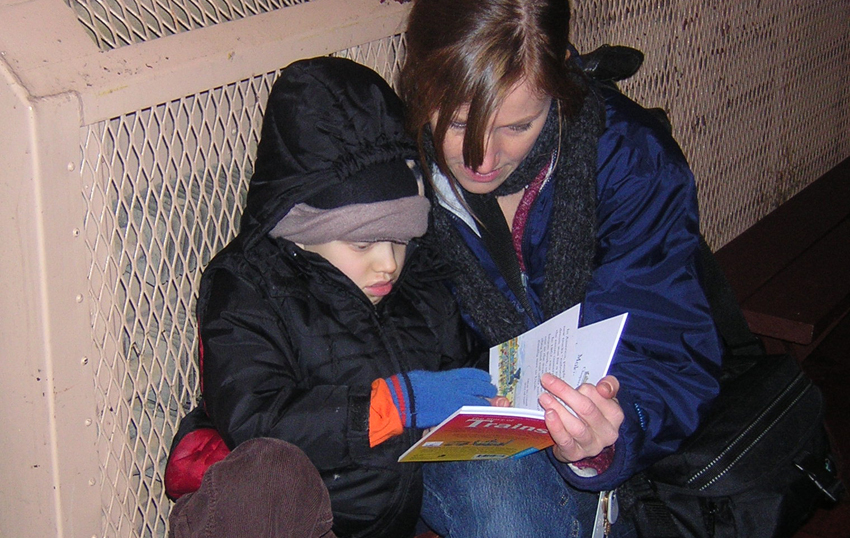

The actual, heavy, real work of grieving is not something you can do (see #1), but you can lessen the burden of “normal” life requirements for your friend. Are there recurring tasks or chores that you might do? Things like walking the dog, refilling prescriptions, shoveling snow and bringing in the mail are all good choices. Support your friend in small, ordinary ways — these things are tangible evidence of love.

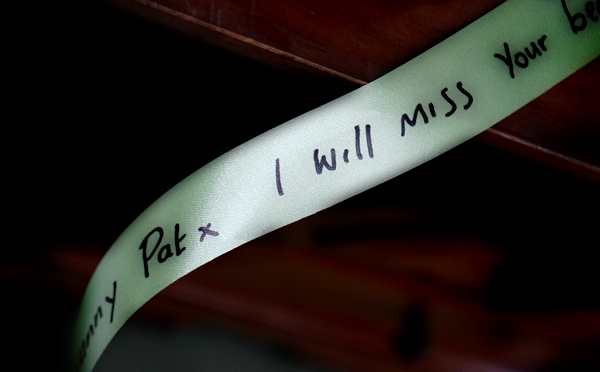

Please try not to do anything that is irreversible — like doing laundry or cleaning up the house — unless you check with your friend first. That empty soda bottle beside the couch may look like trash, but may have been left there by their husband just the other day. The dirty laundry may be the last thing that smells like her. Do you see where I’m going here? Tiny little normal things become precious. Ask first.

#8 Tackle projects together.

Depending on the circumstance, there may be difficult tasks that need tending — things like casket shopping, mortuary visits, the packing and sorting of rooms or houses. Offer your assistance and follow through with your offers. Follow your friend’s lead in these tasks. Your presence alongside them is powerful and important; words are often unnecessary. Remember #4: bear witness and be there.

#9 Run interference.

To the new griever, the influx of people who want to show their support can be seriously overwhelming. What is an intensely personal and private time can begin to feel like living in a fish bowl. There might be ways you can shield and shelter your friend by setting yourself up as the designated point person — the one who relays information to the outside world, or organizes well-wishers. Gatekeepers are really helpful.

#10 Educate and advocate.

You may find that other friends, family members and casual acquaintances ask for information about your friend. You can, in this capacity, be a great educator, albeit subtly. You can normalize grief with responses like,”She has better moments and worse moments and will for quite some time. An intense loss changes every detail of your life.” If someone asks you about your friend a little further down the road, you might say things like, “Grief never really stops. It is something you carry with you in different ways.”

#11 Love.

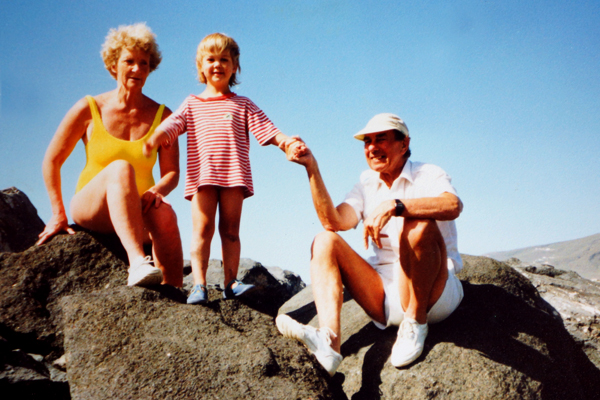

Above all, show your love. Show up. Say something. Do something. Be willing to stand beside the gaping hole that has opened in your friend’s life, without flinching or turning away. Be willing to not have any answers. Listen. Be there. Be present. Be a friend. Be love. Love is the thing that lasts.

Megan Devine is the author of Everything is Not Okay: an audio program for grief. She is a licensed clinical counselor, writer and grief advocate. You can find her at www.refugeingrief.com. Join her on facebook at www.facebook.com/refugeingrief